Thursday, January 29, 2015

Monday, January 19, 2015

Walter Van Beirendonck S/S 15 MENSWEAR

The Crazy Cool Chic of an Independent - Original -Thinker.....adding much needed whimsy and humor to a free spirited, confident man's wardrobe. The Belgian designers happily march to their own drumbeat and continually surprise and delight.

Saturday, January 17, 2015

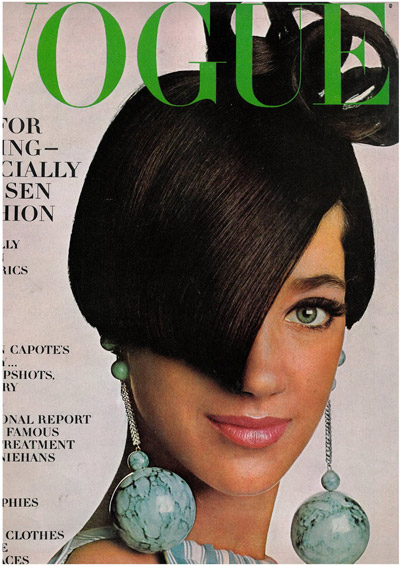

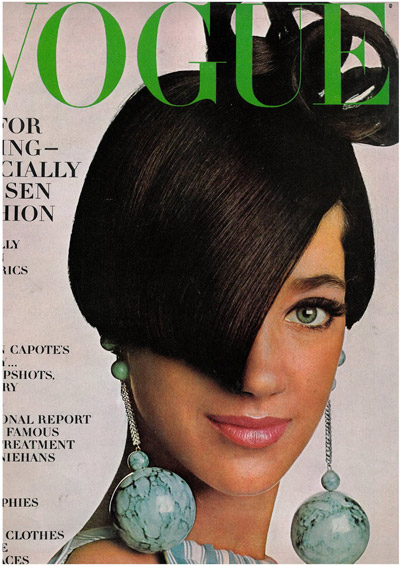

60's Vogue Icon: Marisa Berenson

An icon of 1960's Vogue Fantasy editorials, Miss Berenson was a favorite Vreeland dress up ( and undress!) doll. Mrs Vreeland adored jet set party girls from socially prominent families which also allowed her access to the most beautiful homes and gardens for her Vogue shoots.

Hedonism was a central theme in the 60's drug fueled youthquake era, where innocent nudity was glamorized and hair and make up artists went wild in their creativity.

Travel to exotic destinations was encouraged by shoots done in impossible to get to mountain tops and extra secluded beaches....all to help the Vogue reader escape the mundane routine of daily life.

Miss Berenson was born in New York City, the elder of two daughters. Her father, Robert Lawrence Berenson, was an American career diplomat turned shipping executive of Lithuanian Jewish descent, and his family's original surname was Valvrojenski.[1][2] Her mother was born Maria Luisa Yvonne Radha de Wendt de Kerlor, better known as Gogo Schiaparelli, and was a socialite of Italian, Swiss, French, and Egyptian ancestry.[3][4]

Hedonism was a central theme in the 60's drug fueled youthquake era, where innocent nudity was glamorized and hair and make up artists went wild in their creativity.

Travel to exotic destinations was encouraged by shoots done in impossible to get to mountain tops and extra secluded beaches....all to help the Vogue reader escape the mundane routine of daily life.

Miss Berenson was born in New York City, the elder of two daughters. Her father, Robert Lawrence Berenson, was an American career diplomat turned shipping executive of Lithuanian Jewish descent, and his family's original surname was Valvrojenski.[1][2] Her mother was born Maria Luisa Yvonne Radha de Wendt de Kerlor, better known as Gogo Schiaparelli, and was a socialite of Italian, Swiss, French, and Egyptian ancestry.[3][4]

Berenson's maternal grandmother was the fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli,[5] and her maternal grandfather was Wilhelm de Wendt de Kerlor, a theosophist and psychic medium.[3][6][7] Her younger sister, Berinthia, became a model, actress, and photographer as Berry Berenson. She also is a great-grandniece of Giovanni Schiaparelli, an Italian astronomer who believed he had discovered the supposed canals of Mars, and a second cousin, once removed, of art expert Bernard Berenson (1865–1959) and his sister Senda Berenson (1868–1954), an athlete and educator who was one of the first two women elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame.[8]

Monday, January 12, 2015

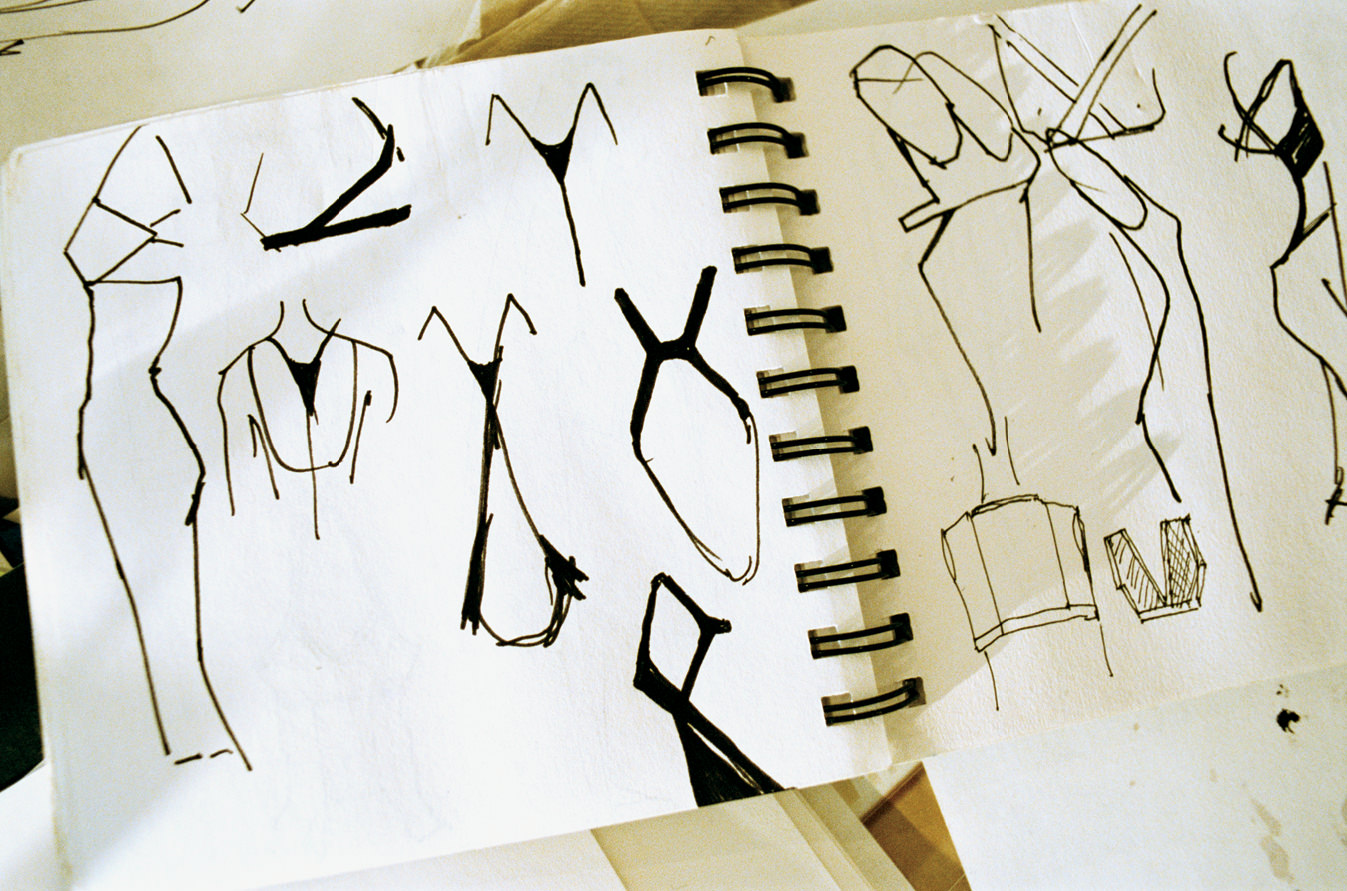

QUICK! Sketch Artist: Joe Eula

Kathy Horyn on Her New Joe Eula Book

by Lolasouthwell Lola fashionpeople

Cathy Horyn’s new book, Joe Eula: Master of Twentieth-Century Fashion Illustration, focuses on a figure who at first glance seems rather more marginal than his friends and contemporaries, Halston and Warhol, but who turns out to be one of the great catalysts of his era. Eula may be best known as an illustrator—his drawings accompanied Eugenia Sheppard’s famous fashion column in the New York Herald Tribune and he created memorable posters and album covers for Liza Minnelli and Miles Davis—but he had many more strings to his bow. A World War II veteran, he was a stylist and creative partner to the celebrity portrait photographer Milton H. Greene in the 1960s, and he was a key figure in the combustible, productive scene that was Halston’s studio in the ’70s. Even if he were only remembered for the parties he threw at his East 54th Street apartment during this period, that would be enough to ensure his place in history, given that on any night you might run into Lauren Bacall, Anjelica Huston, Diana Vreeland, Loulou de La Falaise, and Marisa Berenson. For Horyn, who befriended Eula toward the end of his long life and was a frequent guest at his country house in Hurley, New York, this uncategorizable, talented man was a precursor to today’s generation of multi-hyphenate creative types. I called her up to talk about Eula and the book, though along the way we also got into John Galliano, Oscar de la Renta, Marc Jacobs, and the merits of German health clinics.

How would you describe Joe?

The thought that comes to mind is an absolute character. I mean, you think of the parties that he had on 54th Street. They were kind of a preamble to going to Studio 54. Joe was loud, he was quick. If you started a conversation with Joe, you thought, My God, he just knows everybody and anything … And he had such good, modern ideas about things. He was really an evergreen personality. He didn’t age, his ideas certainly didn’t age, and it made you understand why so many people sought out Joe for work or opinions. He just had a really great sense of what was American and what was modern. And he managed to strip everything back to what was the essence of something. And he could do that in his conversations, as well as his drawings, as well as his ideas about what looked good on a woman. I mean, I could see him sitting there, shoulder to shoulder with Halston and the people in Halston’s studio, and Joe saying, “Nah, don’t do that.” He was very much a live wire; you felt like he was always on. But at the same time, you never got tired of being around him. He actually was very warm and mellow in a way and humble.

To what extent did Joe help focus Halston’s aesthetic?

Certainly Halston had great ideas, but I think China Machado has some good points about the fact that Joe allowed Halston to be outrageous in a way. He kind of tickled that in Halston. I went back and looked at the reviews of Halston’s first shows. These are the ones I think when Bergdorf sort of backed him in that early effort, and the clothes were very comme il faut. They weren’t what you think of as the Halston of the late ’60s and ’70s. So yeah, you do wonder where Joe’s influence came into that. And also I do trust Fernando Sanchez … He lived in the same building where Joe lived, in the Osborne. Much grander apartment. And I remember Fernando saying that without Joe and without Elsa [Peretti], Halston would never have been the success that he was … [But] I also talked to one of the few surviving guys who worked in the studio in those early days, Enrique Maza. He kind of wondered about what Joe really did, and Nancy North was another person who kind of questioned how much Joe did. Because I think also then drugs start entering into the scene and very high tempers and lots of money, and I think things start breaking down a bit.

Why does that era seem so endlessly fascinating?

I think it was just so free. It was so glamorous. You look at who came to Joe’s apartment … and the kind of informality of Joe’s apartment and the way he entertained people. I think that is one of the attractions. It makes me think of a completely different subject. You know, with Ben Bradlee dying, people have been trying to put their finger on why Ben was such a good editor. And I think he hired good people and let them do their job … These people, they knew what was right to do. I mean, it’s hard to compare Joe Eula and Ben Bradlee, they are completely apples and oranges. But we are so complicated by things now. We have so many more rules and there is political correctness, and both these guys were opposed to things like that, and Joe was always looking out for people who were big phonies, and I think that was an element of the appeal. They were able to sort of be the people who they wanted to be and live very full lives … I think the thing about Joe that is interesting and that relates to today a lot is that he did doeverything. The way that a lot of people today do everything. The way that a stylist can end up being a fashion designer, or that a celebrity can have their own fashion label, or somebody can be a photographer and art director and maybe even do something else on the side—that sort of multitasking, multilayered career. Joe did that, and he was doing it in the ’60s.

Was it freeing to write about someone who was, let’s say, more of a character actor than a leading star of his era?

What’s freeing is that there’s more for people to discover. I kind of knew the basic stories, but there was more for me to discover as well. Like his being in World War II. I thought those letters were amazing that he wrote to his mother, calling her Fatty, which I loved. You can hear his voice in there, that’s the way he talked, calling his mum Fatty, you know … but he had a great relationship with her. I think it’s great to be able to introduce an audience of readers to someone like Joe. Time moves so quickly now, and everybody just kind of goes to the icons of a particular era and they forget or they overlook the people who were the character actors and in many ways the catalysts for a particular moment.

Even though Joe wouldn’t be in the top, top tier of illustrators, he could capture a moment in a way that was unique. Was that his main strength as an illustrator?

I think so, yeah. And I don’t think it’s anything to be taken lightly, either. It really was an incredible quality. I think Liza [Minnelli] said it best, that his drawings showed you how the dress was supposed to look, the effect of the dress, and I think that was also kind of particular to Joe. He did a drawing—I think it was forTown & Country—of a Charles James cocktail dress that was just divine. I mean, it was so beautiful, so simple … But it wasn’t like Eric [Carl Erickson], let’s say, and the great illustrators of the prewar and the postwar. Those guys were in Vogueand Bazaar, so they were going to be kept and cherished, and I think when you illustrate for a newspaper, particularly for Eugenia [Sheppard], who was the powerhouse of fashion journalists in the ’50s and ’60s, you had to be quick. You had to get it done so it could make the wire and all that stuff. And I think that just influenced Joe, along with his own personality. I do think you have to be honest about Joe—some of his drawings are awful, that’s just the nature of it, and I think as he got older, there was a sort of caricature quality to his drawings. And that’s just the nature of the amount of work that he did. But then if you look at his watercolors, his drawings of flowers, which he did later in life, they are gorgeous. They are just some of the best things. And his roosters that he did for Tiffany. Those plates are very difficult to get now and are very expensive to get. It just shows you the whole breadth of a career.

And there were the posters he did for movies or nightclubs. They were sort of witty …

I loved what he did for The Cheetah [club]. That was so erotic looking … I saw the original drawing of the Miles Davis Sketches of Spain [album cover] and it was just gorgeous.

Going back to Joe’s personality, one of my favorite anecdotes is when he went to a Saint Laurent couture show, but after three looks he got up and said, “This sucks,” and it caused a huge scandal.

Yeah, that was amazing … And then all of the kiss-and-make-up afterward. But it didn’t, strangely, affect his relationship with [Pierre] Bergé or with Yves. They still stayed friends.

Has that been lost a little bit in fashion, that kind of high passion?

Yes, it has. Again, we’ve lost Oscar de la Renta, and Oscar was also somebody who stood his ground about things and could be outspoken about many things. He was a very competitive guy. One time I asked Oscar about his relationship with John Fairchild—this was in 2009—and he just said, “Oh, we had hundreds of disputes.” And I know that’s true. Oscar could get very upset if he didn’t feel John was doing right by him or doing right by somebody else. And particularly there was a rivalry between Oscar and Bill [Blass]. I mean, they were very good friends, but I am talking about a business rivalry. They had the same clients. And I think John Fairchild was brilliant at how to play one person off the other and who was up and who was down and all that kind of stuff, and he did it with socialites, too. But I do think there was more tolerance then. People let things roll off their backs and these relationships were so intimate and people were on the same plane of worldly sophistication.

Before I let you go, I wanted to ask, did you miss going to the shows this season?

Not really. I certainly followed. I kind of tuned in for the key shows in New York and Milan and Paris. But I didn’t miss the running around part, that’s for sure. I didn’t miss the pressure that everyone’s under now to get a lot of stuff online quickly, which you know very well. I think that part is really grinding. It’s fun to sort of have more time, actually, and have more distance from it.

Any favorites this season?

In New York I loved Marc Jacobs. I mean, he repeated a lot of things, but those first 10 to 15 looks were really great.

That’s interesting, because when you were there, that giant set and listening on the headphones made for a very immersive experience, but it almost took away from the clothes.

I heard that from other people. And I heard other people say that they were bored by it, that it was very repetitive. And it was weird because I went online the morning after the show, and I didn’t know what the set was, except that it was pink or something, and I just thought this is really great, this sort of utilitarian, simple gold dress and then these khaki looks, the jumpsuits, the long dress that almost looked like a jumpsuit in a way, the slight military influence. And then the pantsuit that he did in blue linen, it looked like cadet blue linen, with the belt and wide trousers. And I thought you could see a smart-looking woman in her 60s wearing that. And those little funny khaki dresses at the beginning, they weren’t too far above the knees, so you could see a lot of different people of different ages wearing that. It caught my eye. You know I have seasons where I am really not into Jacobs, but I was into this one. And I thought Dior was really interesting. The way [Raf Simons] picked up from couture those ideas, mixing the historical and the new. I thought the smocky weird dresses were really cool and odd. And again, you have to take it out of the context of the show and put it on the street with a pair of sandals and it’s a really cool look. And I thought Miuccia [Prada] kind of made an interesting statement with her take on classics. And also Nicolas [Ghesquière], I really liked that, too. He stayed on the same wavelength from last season—I thought that was smart—but he added more depth to it. It kind of talked to me a little bit, and then I kind of got off on other things to work on. So I’ll circle back again.

Any thoughts on John Galliano at Margiela?

It seemed to me more of a publicity move than anything—good for Renzo [Rosso] and good for that particular brand. I think there is a connection between John and Margiela, actually. You know, Margiela in his prime was great at making a statement about clothes and what they did or didn’t do. He was good at staging a show and John is also great at staging a show, so there is a connection there. I think people shouldn’t have too high of an expectation about how much John will really do at Margiela. I think he will do a lot in terms of the shows and the collection, but beyond that I don’t know. One should remain skeptical about that, I think. But I think it is good that John has a chance to get back in there and reclaim his reputation. And you know, he has a lot riding on this. No matter where he would land, he has to really show that he has got the discipline and that he’s got all the things that people would expect today. And I would assume that Renzo will give him the freedom to be as creative as people want John to be. So a lot of things have to fall into place for it to really work. But my initial thought was that it was a fairly shrewd publicity move for Renzo. It brings a lot of attention to Margiela. And you can argue that that’s not good. But it’s not a question of good or bad, it’s just a reality.

Anything else you’re working on at the moment?

I have a fun piece coming out in T. I took this trip to Germany. I went to one of those … you know, those German clinics? [laughs] It’s called “Purge and Binge” and it’s coming out in T and that’s all I’ll say! And then I am working on theTimes book, too. That’s my main project right now. It’s going to take a while.

Illustrations and photographs from Joe Eula: Master of Twentieth-Century Fashion Illustration by Cathy Horyn. Copyright 2014 by Melisa Gosnell. Images reprinted courtesy of Harper Design, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Mr.Eula strength was capturing the mood, silhouette, color and pattern in 30 SECONDS ...or LESS!lol

The irreplaceable Pat Cleveland in Halston RED, proves why she was the star of the "Halstonettes"...the band of a dozen models who fluttered around the designer for press.

Sunday, January 11, 2015

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)